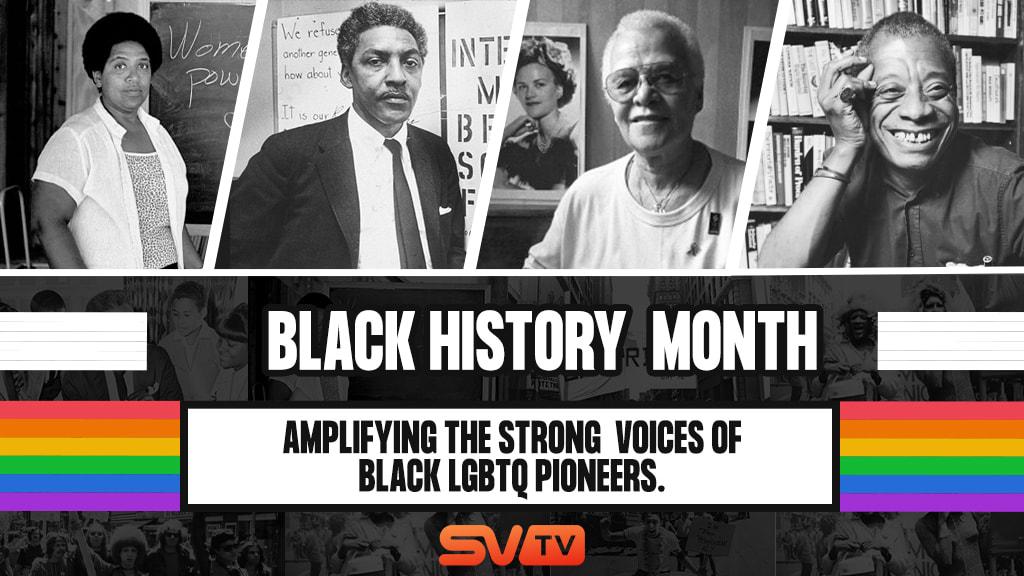

Black History LGBTQ Heroes

The SVTV Network celebrates Black History Month by amplifying the voices of Black LGBTQ heroes. Those who have paved the way for an entire community.

Every nation has people who work extraordinarily for their development and progress. We generally call these people heroes. A hero is a person who finds the strength to continue and endure in the face of adversity.

Here you will find our LGBTQ heroes as follows.

James Baldwin

James Arthur Baldwin was an essayist, dramatist, novelist, civil rights activist, speaker, and significant poet. His study contributed to a better understanding of race relations in the United States in the mid-twentieth century. Race, religion, and sexualities were all general topics in his writing. His books were sometimes semi-autobiographical, brimming with his and others’ pleasures and sorrows. He offered his loud voice to the civil rights struggle as a civil rights activist, and many saw him as a keen authority on questions of race in the United States.

He became a priest at Fireside Pentecostal Assembly at the age of fourteen. His presence brought many people, which was suitable for the congregation. He appreciated this environment and the respect he earned as a result of it at first. But he soon came to doubt the Bible’s accuracy and the church’s use of his gifts. He quit the ministry at the age of sixteen in 1941, after preaching for three years.

Baldwin’s sexuality pressed against him as he walked out of the chapel. He quickly relocated to Greenwich Village. There he resided with his mentor, Harlem Renaissance modernist painter Beauford Delaney. He began to explore his sexuality in the Village. Even though he had found some independence there, his stepfather’s death and his mother’s deteriorating health necessitated regular travels home. In 1943, Daniel Baldwin, Sr., passed away.

The native son continued to struggle for racial justice in the United States while in Europe in 1965. He advocated for the release of the Harlem Six, a group of men accused of first-degree murder who were deemed wrongly convicted. In 1970, he strongly condemned the arrest of political activist Angela Davis. “For if they kidnap you in the morning, they will come for us that night,” he said in an open letter to her. Baldwin continues to participate in and organize social and political reform protests. His outspoken political writings and support for Black Panther Party and Communist Party activist Angela Davis earned him “radical.”

Baldwin continued to write during the 1970s and 1980s, his most recent work being Just Above My Head (1979). It harkens back to his adolescence and emerging sexuality, with LGBT characters and themes. He also wrote The Price of the Ticket, a compilation of articles about race relations during the previous four decades. He then became a university professor, where he influenced a new generation of authors. Baldwin received various fellowships throughout his life, including a Guggenheim Fellowship. Baldwin died in France on December 1, 1987. His beloved Harlem bid him farewell, and he was laid to rest in Ferncliff Cemetery.

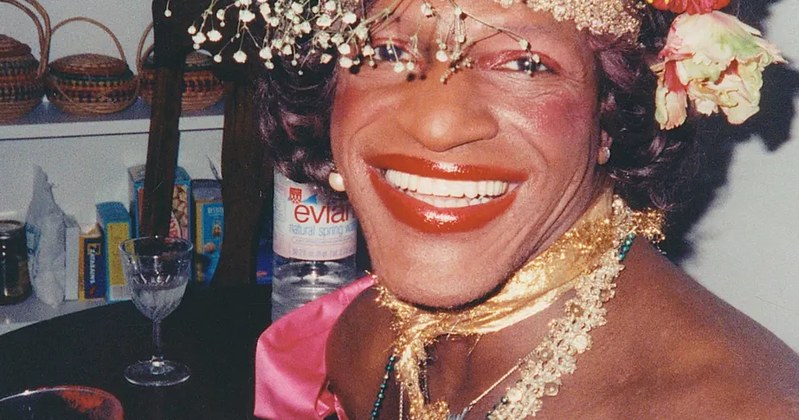

Marsha P. Johnson

Marsha P. Johnson, a transwoman, rose to prominence in the transgender, bisexual, lesbian, and gay communities of New York City. She was unafraid of the abuse that came with living and dressing as a woman but possessing male characteristics.

Marsha knew what it was like to be a transgender person living a hard life full of the desperation of living a life.

When people asked Marsha what her middle name was, she said, “Pay it no mind.” She avoided the public asking the question she loathed by inserting “pay it no mind” in her name. This reply was intended as a bombastic response to whether she was a man or a woman, which was on many people’s minds.

Marsha P. Johnson thought that these people required the support of the growing LGBT community. She struggled to help individuals working in an unaccepting society.

Marsha was an unorthodox woman noted for her unique jewelry and headgear that drew attention to her. Marsha P. Johnson was Marsha P. Johnson when she wore these things or any feminine apparel. But there were occasions when she reverted to Malcolm, her masculine character.

Marsha did a series of paintings and images and her STAR and GLF activity. One of Warhol’s pieces for which Marsha appeared in 1975 was titled “Ladies and Gentlemen.” Marsha, as well as the other male-to-female transgender people, are not named in the image. “If ‘giving face’ via portraiture implies a person’s recognizability, then this portfolio was doomed from the start, for the women and gentlemen shown here have no legitimate names,” Taro Nettleton argues.

In July 1992, her body was found from a river named Hudson in New York. Investigations revealed a suicidal attempt, but the people who knew Marsha rejected these investigations.

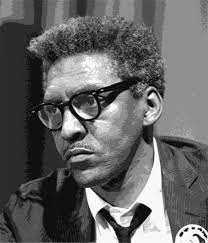

Bayard Rustin

His family was prominent in civil rights advocacy in Pennsylvania, where he was raised. He moved to Harlem in 1936, where he performed as a stage and nightclub performer while advocating for racial rights.

Rustin was a pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) member advocating nonviolence. He played a vital role in the civil rights movement, assisting in planning the 1947 Freedom Ride.

Rustin taught nonviolence and peaceful resistance. In 1963, he was the primary organizer of a notable African American labor leader and communist. He helped form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to support King’s leadership. Rustin was a pivotal player in the civil rights struggle from 1955 until 1968.

Rustin was a gay guy arrested in 1953 for committing homosexual conduct. Until 2003, homosexuality was illegal in several regions of the United States.

He was on a humanitarian trip in Haiti at his death in 1987. Rustin only functioned as a public spokesperson to prevent such assaults on rare occasions. Rustin was a gay man who, because of his sexuality, generally served as an influential consultant to civil-rights leaders behind the scenes.

Barbara Jordan

Barbara Jordan (1936-1996) was the first LGBTQ woman to be elected to Congress. Jordan was a great lawmaker, civil rights activist, and teacher. She was born in the historically Black Fifth Ward of Houston.

Jordan was unable to attend the University of Texas in Austin owing to segregation. She graduated from Boston University School of Legal and returned to Houston in 1960 to start a law firm after teaching at the Tuskegee Institute.

Jordan was elected to the Texas Senate for the first time since the end of Reconstruction in 1883, in 1966. She became the first woman to represent Texas in the United States House of Representatives when elected in 1972.

One of Jordan’s most memorable activities in Congress was her 15-minute televised address to the House Judiciary Committee members during the Nixon impeachment hearings on July 25, 1974.

Jordan’s dedication to public service came at the expense of concealing her inner self, particularly her sexuality, which remained unknown until her death in the Houston Chronicle. When Nancy Earl died of illness in 1996, she was Jordan’s “longtime friend.” Even though they had spent decades together—the two met on a camping trip in the 1960s and lived in a house they built in Austin until Jordan’s death—Jordan had never publicly acknowledged Earl as her companion.

Jordan died on January 17, 1996, in Austin, Texas, from pneumonia complications at 59.

Angela Davis

A former political prisoner, a renowned philosopher of freedom, and a queer Black woman, scholar, and activist. Angela Davis can be described in a variety of ways.

Davis grew up in segregated Alabama, where he was born in 1944.

Her early politics were influenced by the terrible political, racial, and economic inequality she encountered, as well as the organizations she observed pushing for change. The Communist Party was one among them, with a long history of mobilizing for reform in the South.

Davis, a bright student, won a scholarship to a progressive high school in New York City. Her undergraduate studies were at Brandeis University in Boston, where she studied political theorist Herbert Marcuse. She went on to study philosophy at the Sorbonne in Paris and then began her Ph.D. studies in West Germany.

Davis was motivated to return to the United States to join the rising Black Power movement. She relocated to Southern California, temporarily working with the Black Panthers before focusing on the Che-Lumumba Club, an all-Black Communist Party chapter.

Angela Davis’s political ideals might jeopardize her academic career in 1969. She was hired as a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, but was shortly sacked owing to her Communist Party membership. The university’s decision prompted a nationwide discussion over academic freedom and put Davis in the spotlight.

Davis, a talented scholar and political thinker became a vocal activist in the Black community of Los Angeles. She became a symbol, both as a political person and a model of Black femininity.

Angela Davis would inspire activists and artists all around the country and the world by 1970. The posters created during this period exhibited the cross-pollination of Black Power, counterculture, and pop culture influences.

Angela Davis went on to work as a lecturer, author, and public intellectual after being found innocent and released from jail in 1972. She continued to be active in anti-racist and anti-capitalist thought and organization and spoke out against state brutality, imperialism, and the criminal justice system.

Angela Davis, who has been a significant philosopher of liberation for the past five decades, is still vocal. Davis now aims at mainstream LGBTQ movements, arguing that the military and marriage should be scrutinized as institutions tainted by sexism, homophobia, and capitalism.

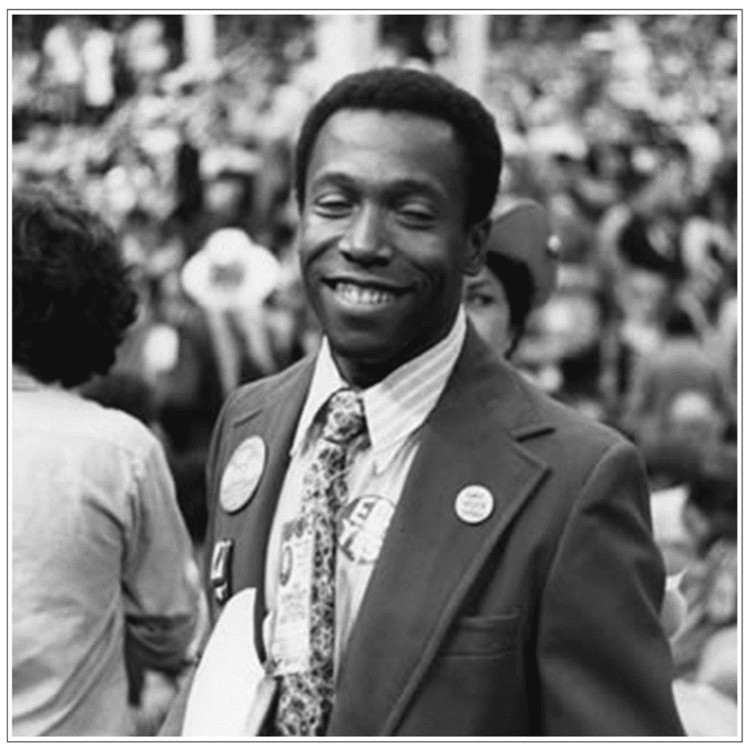

Mel Boozer

Melvin Boozer was born o June 21, 1945. Boozer grew raised in Washington, D.C., where he attended Dunbar High School and became salutatorian of his class. Boozer was a scholarship student at Dartmouth College, one of three African Americans enrolled that year. He went on to Yale University to pursue a Ph.D. before becoming a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland.

Boozer was chosen president of the Gay Activists Alliance of Washington, D.C. in 1979, and he spent two one-year terms in that position. He was the first African American to be elected president of the GAA, and he became known as “a prominent moderate voice among black gays across the country.” The Sexual Assault Reform Act, which decriminalized sodomy and eliminated solicitation restrictions for consenting people, was unanimously passed by the D.C. Council when I was president of the GAA. Congress used its ability to override D.C. actions for the second time to rescind this move under pressure from the Moral Majority, a Christian proper lobbying organization. During his tenure as president, the GAA secured permission to lay a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknowns at Arlington National Cemetery and won a legal struggle with the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority over the placement of “Someone in Your Life is Gay” Metrobus posters.

Boozer was nominated for Vice President of the United States by the Socialist Party USA and the Democratic Party, respectively, at the 1980 Democratic National Convention. He was the first openly homosexual candidate to be nominated for the position.

Before the balloting was terminated, Boozer garnered 49 votes, and Vice President Walter Mondale was renominated by acclamation.

Boozer was appointed as a district director and lobbyist by the National Gay Task Force in 1981. In 1983, he was ousted by NGTF executive director Virginia Apuzzo, who replaced him with then-GAA president Jeff Levi. This resulted in “the nation’s oldest homosexual group becoming increasingly whiter,” prompting fellow LGBT African Americans outrage.

He co-founded the Langston Hughes–Eleanor Roosevelt Democratic Club in 1982 to campaign for black LGBT individuals in Washington, D.C. He served as its president in 1983 and 1984.

Boozer died in Washington, D.C., in March 1987, at the age of 41, of an AIDS-related illness. He is commemorated on a panel of the AIDS Memorial Quilt.

Boozer was honored on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor at the Stonewall National Monument (SNM) in New York City’s Stonewall Inn in June 2019 as one of the first fifty American “pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes.” The Stonewall National Monument is the first national monument devoted to LGBTQ rights and history in the United States. The wall’s dedication coincided with the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.